Kafka replication deep dive

[INFO]

The post covers replication for Kafka version (>=3.7).

Introduction

Like any serious distributed storage, Kafka provides numerous ways of configuring durability and availability. You’ve heard it a million times, but I’ll repeat it the (million + 1) time: in a distributed system world some of the nodes will inevitably fail. Even if the hardware doesn’t break, there are still other threats: power outage, OS restart, network separation from the rest of the system. Fortunately, Kafka has the right mechanisms in place to overcome the problems. We will explore Kafka replication, enabling us to set up a system adjusted for specific requirements while gaining insight into the internals.

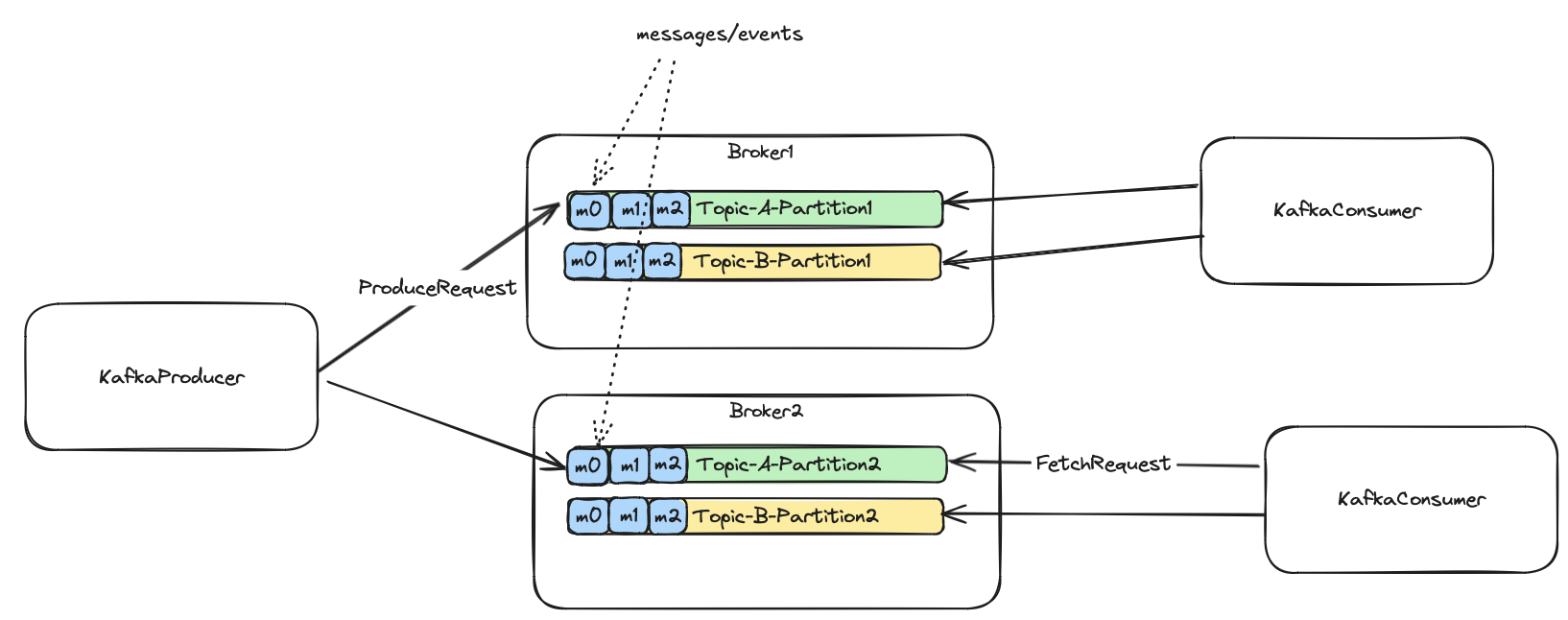

Topics, Partitions, Brokers

Kafka divides published messages into a set of topics. A topic is just an abstraction for one category of related messages. It’s something like an SQL table or database collection. The topic is divided into partitions. Partitions are distributed across different machines (brokers). Partitions are a way to achieve scalability because clients can publish/consume messages to many partitions in parallel. We’ll cover it in a second. The messages are guaranteed to be read in the same order as they were written within a single topic partition.

How to choose a number of partitions

When choosing the number of partitions there is a general advice: calculate it. You can then set a little higher number when anticipating growth. Keep in mind, that you can only increase the number of partitions. Kafka denies decreasing this number. The number of partitions most of the time depends on the speed of consumers consuming from Kafka. Before the calculation, let’s assume the simplified statement: that a single partition can be consumed only by one consumer. Those of you familiar with consumer groups know that it is true only within a single consumer group. So for example, if a single consumer’s max throughput is 100 m/s (messages per second) and expected incoming traffic to a Kafka topic is 500 m/s, you will need at least 5 consumers running in parallel. Because a single partition can be handled by a single consumer, we’ll need at least 5 Kafka partitions.

[INFO]

I purposely focus only on the consuming side in the calculation. We didn’t take into account if that number of partitions is enough for writing provided throughput. I assume that most of the time the bottleneck will be the consuming application rather than Kafka itself. We can scale number of producers independently of the number of partitions, but the parallel consumers are limited by the number of partitions.

The general advice is: partitionsCount = expectedThroughput / throughputOfASingleConsumer

Increasing availability and durability - partition leaders and followers

For better produce/consume scalability we can bump up the number of partitions, but what happens when one of the machines hosting

a partition fails or restarts? You may think: “I can configure the KafkaProducer to omit the failed partition” from

publishing. Well, maybe, but what about already published messages? What about consumers waiting for these messages?

What if the disk crashed permanently? We need something better - redundancy of course.

Each partition is replicated to a configured number of replicas. Each partition has only one leader replica at a time. The leader can change depending on its availability. The producer publishes messages directly to the leader, and similarly, the consumers fetch messages from the leaders. Although there is an option to consume from followers, we do not consider this here.

When creating a topic we provide at least two basic parameters: partitions and replication factor. The former is

a number of partitions a topic is divided into. The latter indicates the replicas count for each partition.

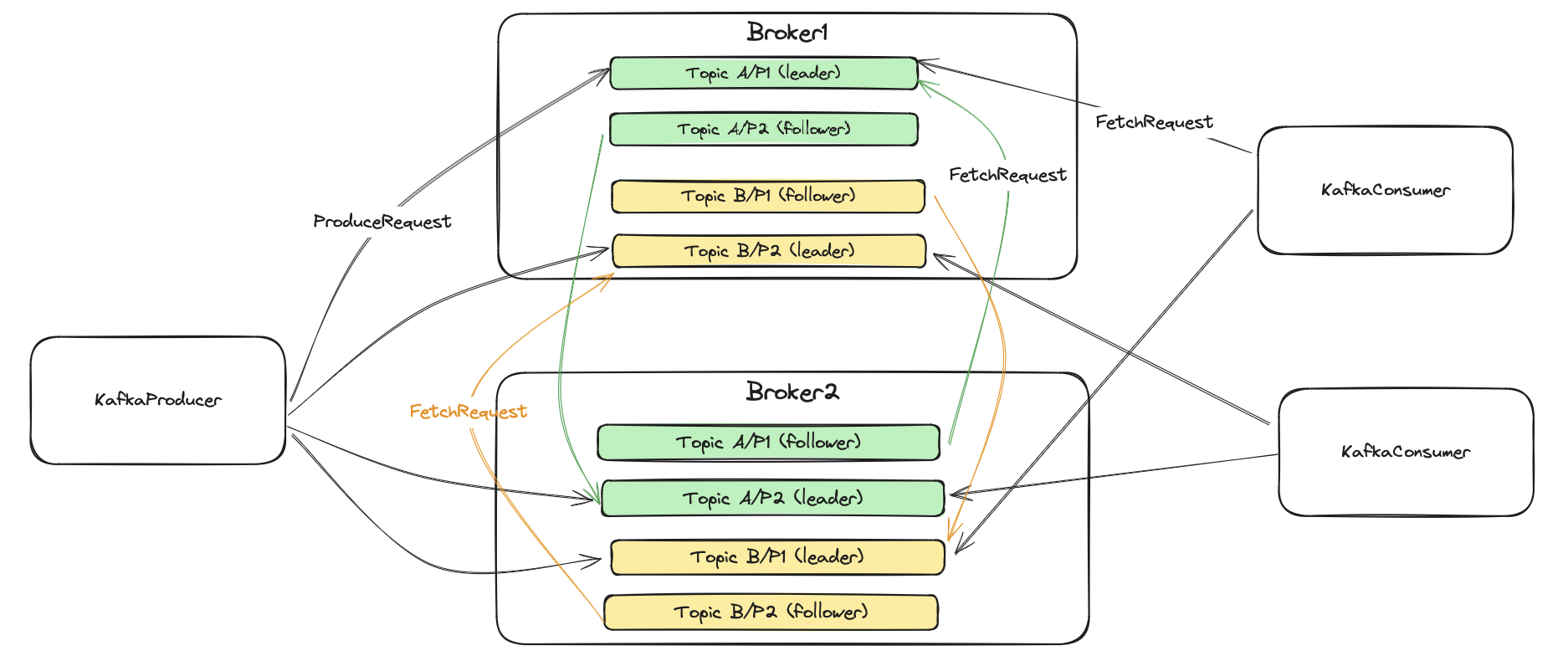

The picture above has two topics with the following configuration:

- TopicA - partitions: 2 (P1/P2) replication factor: 2 (leader and one follower)

- TopicB - partitions: 2 (P1/P2) replication factor: 2 (leader and one follower)

So for example, Topic A/P1 (leader) means a leader replica of partition P1 for topic A.

As you may see, we have a few types of requests here. The ProduceRequest is used by the KafkaProducer to publish

events to the partition leaders. The FetchRequest is used by both, the consumers, and follower replicas to consume/replicate events.

Similarly to the consumers, follower replicas fetch messages from their partition leaders.

A command to create the topic:

./kafka-topics.sh --create --topic A --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --replication-factor 2 --partitions 2

A command to see topic details:

./kafka-topics.sh --describe --topic A --bootstrap-server localhost:9092

Topic: A TopicId: D7DUpsdPTPqXnfigwjKHAg PartitionCount: 2 ReplicationFactor: 2 Configs: segment.bytes=1073741824

Topic: A Partition: 0 Leader: 2 Replicas: 2,3 Isr: 2,3

Topic: A Partition: 1 Leader: 3 Replicas: 3,1 Isr: 3,1

For now, just look at the Topic: A Partition: 0 Leader: 2 Replicas: 2,3 part of the output.

That means that partition 0 of topic A has two replicas situated on broker machines with IDs 2 and 3,

and that the leader replica is a broker 2. I’ll describe the meaning of Isr later.

Kafka brokers and controller

So far, we know that Kafka divides its topics into multiple partitions and that each partition is replicated to the configured number of replicas. We know that partitions are distributed across the cluster’s brokers. We don’t know yet how they are distributed and when the partition to the broker assignment happens. Kafka has two types of brokers: a regular one and a controller. The regular broker hosts partition replicas, serving client’s requests (like produce/fetch requests). The controller, on the other hand, manages the cluster. At this moment, it is important to know that: every time you execute the topic creation command, the request is directed to the controller and the controller assigns partitions to the specific brokers. The controller chooses a partitions’ leaders too.

How does the controller assign new partitions to the brokers? The actual algorithm takes into consideration the number of partitions, replicas, brokers, and racks where the brokers are situated in a server room. Assuming that we have all brokers on the same rack, Kafka controller tries to distribute partitions evenly, so:

- each partition has a leader on a different broker

- each partition has followers on different brokers

The controller spreads partitions using a round-robin algorithm. If you’re curious about the details you can read it here.

Let’s say we want to create a test topic with 3 partitions, each replicated across 3 replicas.

We have also 3 brokers with ids: 1, 2, 3 on the same rack.

----------------- The first node in the assignment is a leader.

|

partition 0: 1, 2, 3

partition 1: 2, 3, 1

partition 2: 3, 1, 2

The first node in an assignment is a leader. The placement assigns brokers to partitions using a round-robin algorithm. Leaders offset by one for each new partition to avoid choosing the same broker for each partition’s leader.

How does it look like in reality?

./kafka-topics.sh --create --topic test --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --replication-factor 3 --partitions 3

Created topic test.

./kafka-topics.sh --describe --topic test --bootstrap-server localhost:9092

Topic: test TopicId: ha0jRlepRvasAGLxmyx60A PartitionCount: 3 ReplicationFactor: 3 Configs: segment.bytes=1073741824

Topic: test Partition: 0 Leader: 1 Replicas: 1,2,3 Isr: 1,2,3

Topic: test Partition: 1 Leader: 2 Replicas: 2,3,1 Isr: 2,3,1

Topic: test Partition: 2 Leader: 3 Replicas: 3,1,2 Isr: 3,1,2

The assignment customization is also possible via Kafka admin tools.

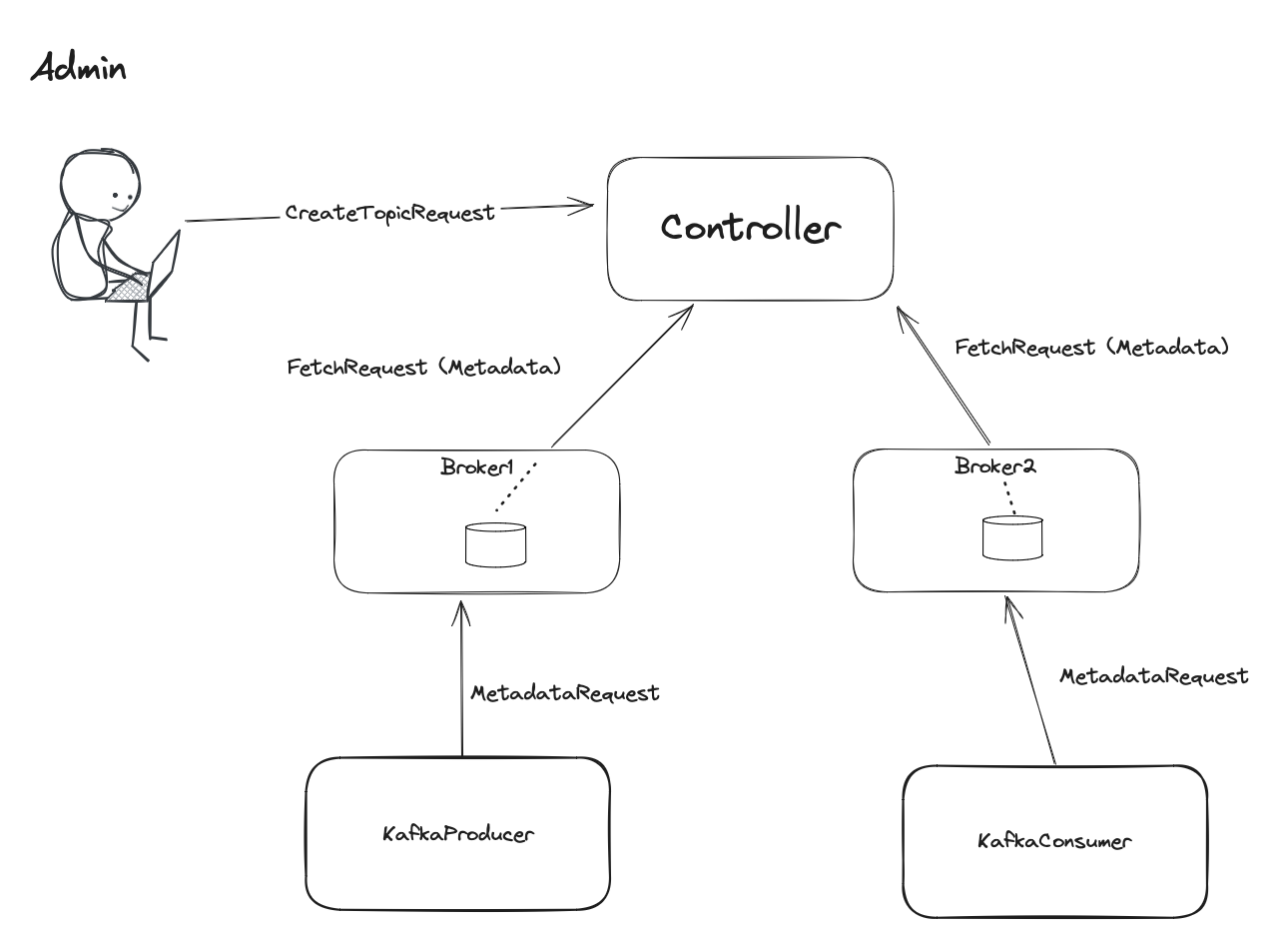

Cluster Metadata

We’ve discovered the topic structure and how the partitions are assigned to the different brokers. The next puzzle

is how the clients know where to send and fetch messages from. As we’ve mentioned, ProduceRequest and FetchRequests

go to the partitions leaders. To find them, clients can send MetadataRequest to any broker in a cluster. Each broker

keeps cluster-wide metadata information on a disk. The usual brokers learn about metadata changes from… Kafka controller.

Every admin change e.g. increasing the number of partitions for a topic goes to the controller. The controller

saves that change on its disk and then propagates it to the usual brokers via metadata fetch API. Then clients learn metadata from the brokers.

In the picture above, the brokers use FetchRequests to get updates about metadata. Internally, metadata is a topic.

Brokers use the existing fetch API to request the newest metadata information. Producers and consumers, on the other

hand, use dedicated MetadataRequest. The response contains information only about interested

topics, their partitions, and leaders. Schema details can be found here

(scroll to the latest version).

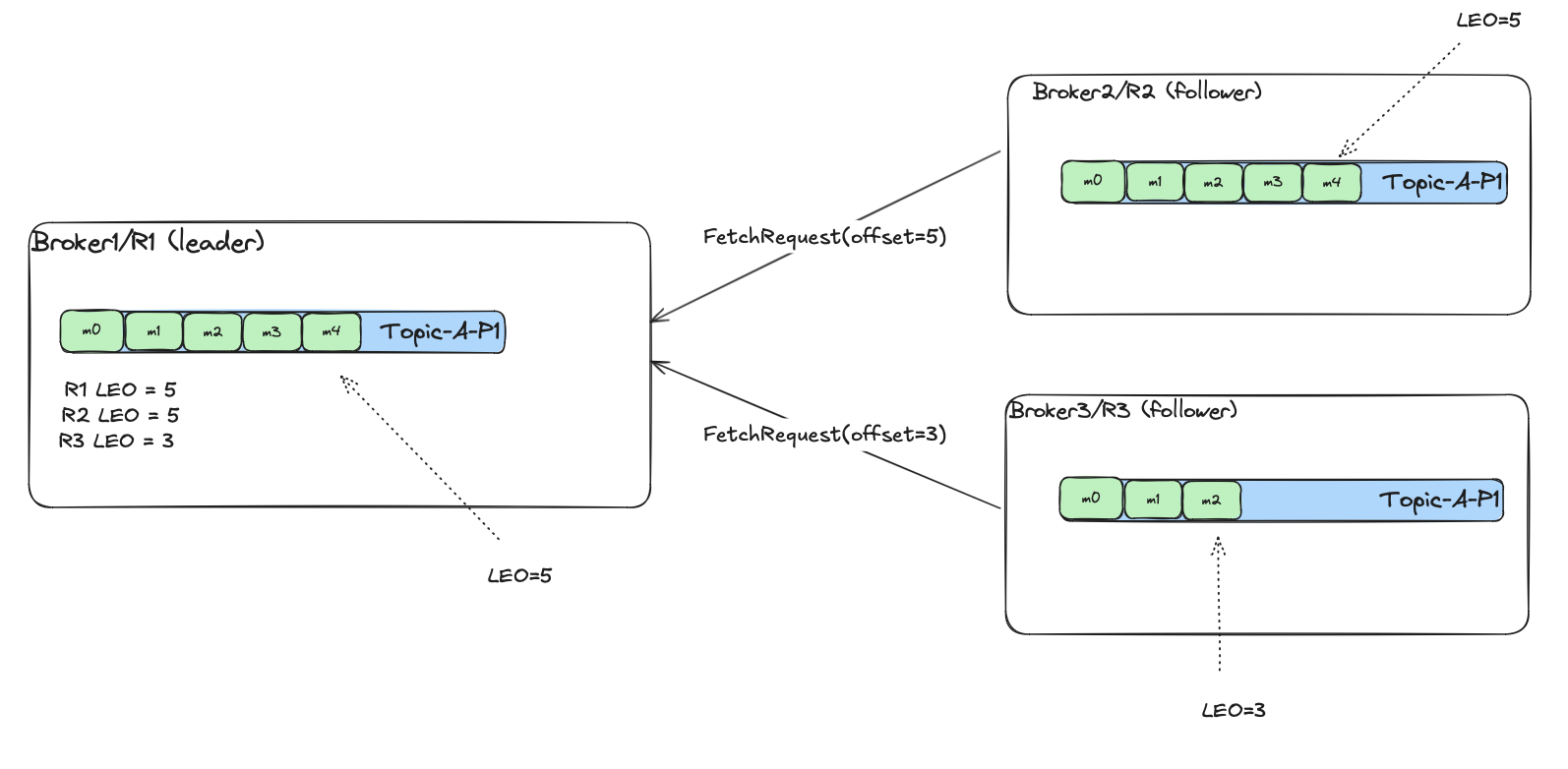

Replication from leader

As I mentioned, the follower replicas use FetchRequest to get messages from the leader. For now,

assume that the only request parameter is offset. So FetchRequest(offset=x) means that:

- the requesting replica wants messages with offsets

>= x - the requesting replica confirms that it persisted locally all messages with offsets

< x - the leader returns messages with offset

>= xto the follower, and saves in its internal state that the requesting follower has all messages with offsets< x.

Each of the replicas may have a different set of messages at a specific point in time.

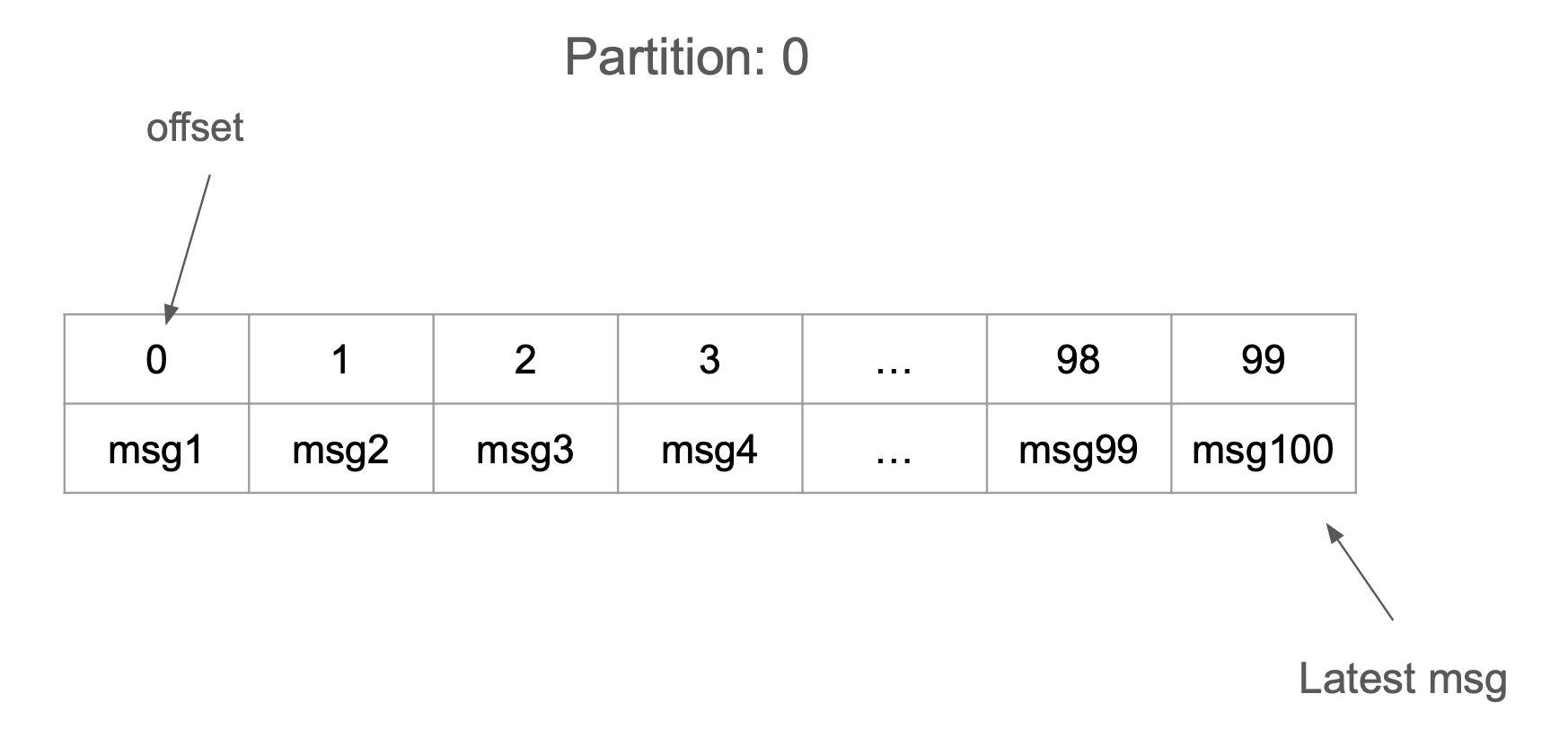

The end of the replica’s log for a partition is called LEO (Log End Offset). It indicates that the replica has

messages with offsets up to the LEO - 1. So LEO is the first offset that the replica doesn’t have yet for a

specific partition. For example, if the replica has a log of messages with offsets [0,1,2,3,4] its LEO=5.

The LEO has many usages in Kafka replication mechanism, we’ll cover that later. One of the usage is tracking the next

offset to fetch as a follower.

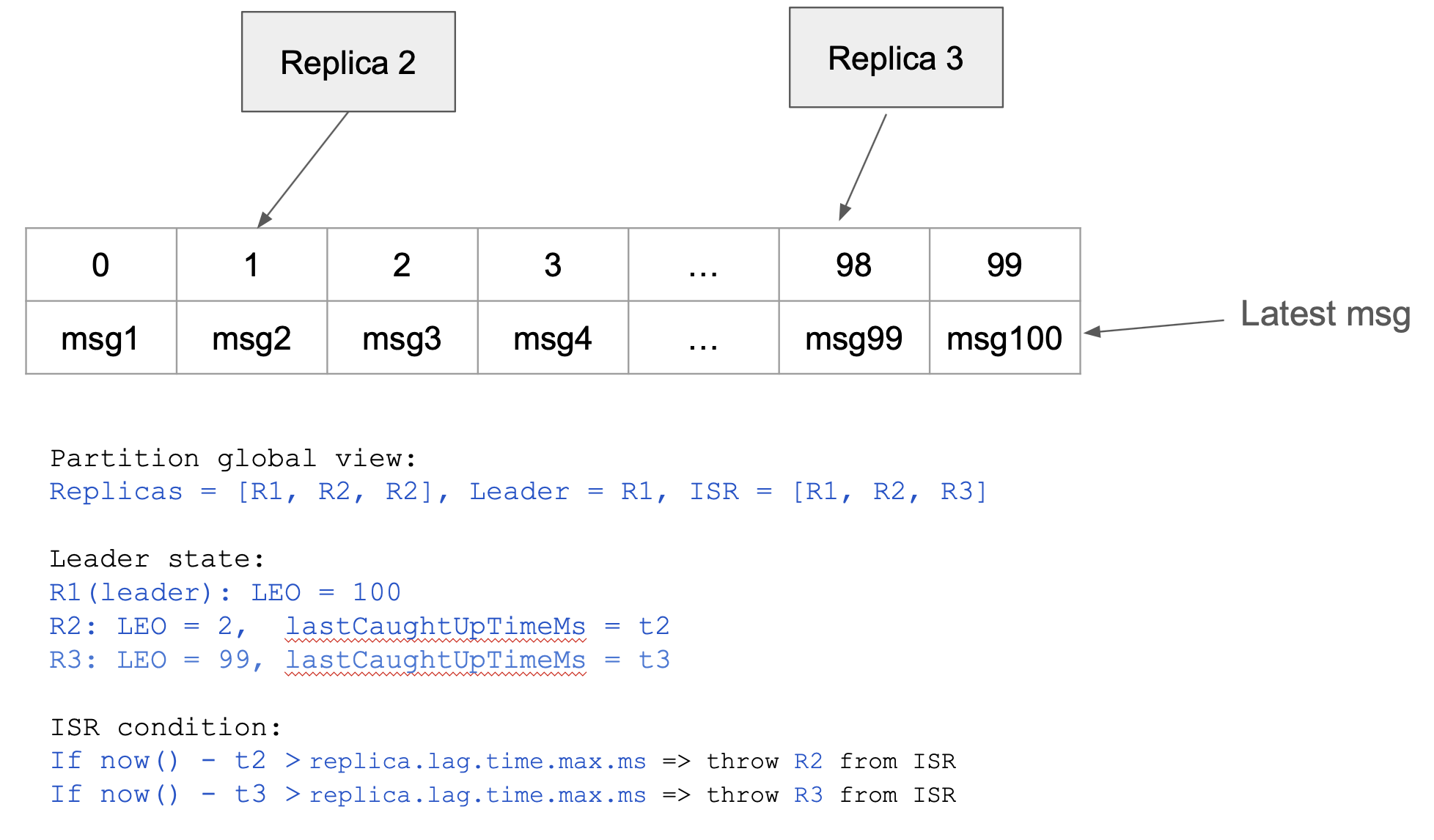

The leader tracks each of the followers’ (and its own) LEO for partition. In the picture above it is

parition P1 of topic A.

Replicas vs In-Sync Replicas

As I explained previously, once the KafkaProducer sends the ProduceRequest to the partition leader, the broker saves

the message, and then follower replicates by fetching it using FetchRequest API. Let’s take as an example the

previously created topic with 3 partitions. For partition 0 there are 3 replicas Replicas: 1,2,3. The leader is 1, the

followers are 2 and 3. Each of the followers has a different pace of replication as they are independent nodes. While replicating,

the leader tracks each of the follower’s replication progress (by using LEO). It can assess which of them are fast and which can’t keep up.

The leader tracks each of the follower’s fetching offset.

![]()

We can now comprehend the concept that Kafka heavily depends on to ensure the safety and correctness of replication: in-sync-replicas (ISR).

For each topic partition, Kafka maintains a curated set of nodes, which are in sync. At a high level, these are the healthy brokers

that can keep up with fetching the newest messages from the leader (where the newest means leader’s LEO). The documentation

says that to be in sync:

1. Brokers must maintain an active session with the controller in order to receive regular metadata updates.

2. Brokers acting as followers must replicate the writes from the leader and not fall "too far" behind.

And there are two broker configs for these conditions:

- broker.session.timeout.ms - The regular brokers inform the controller that they are alive via heartbeat requests. If the time configured as this config passed between two consecutive heartbeat requests, the broker is not in sync anymore.

- replica.lag.time.max.ms -

Each time the same broker fetches messages from a specific topic partition’s leader, and it gets to the end of the leader’s log (

LEO), the leader records the timestamp when that happened. If the time that passed between the current time and the last fetch that got to the end of the log is greater thanreplica.lag.time.max.ms, the replica hosted by the broker is thrown out of in-sync replicas set.

The second timeout is a little bit harder to understand. The picture above shows that replicas R2 and R3 fetch from different

positions from the leader’s log. The Partition state is a global view of the partition in a Kafka cluster.

The Leader state is calculated locally by the partition leader. Each time the replica got to the end of the log

(FetchRequest{offset=100} in this case) the leader sets the lastCaughtUpTimeMs timestamp for that replica.

Then, the leader periodically checks if each replica fulfills ISR condition:

now() - lastCaughtUpTimeMs <= replica.lag.time.max.ms. If not, that replica is thrown out of the ISR. For now, just assume

that the leader somehow changes the global Kafka view of that partition. So for example, if replica R2 falls out of ISR, the

global view of the partition would be like: Replicas: [R1, R2, R3], Leader: R1, ISR = [R1, R3].

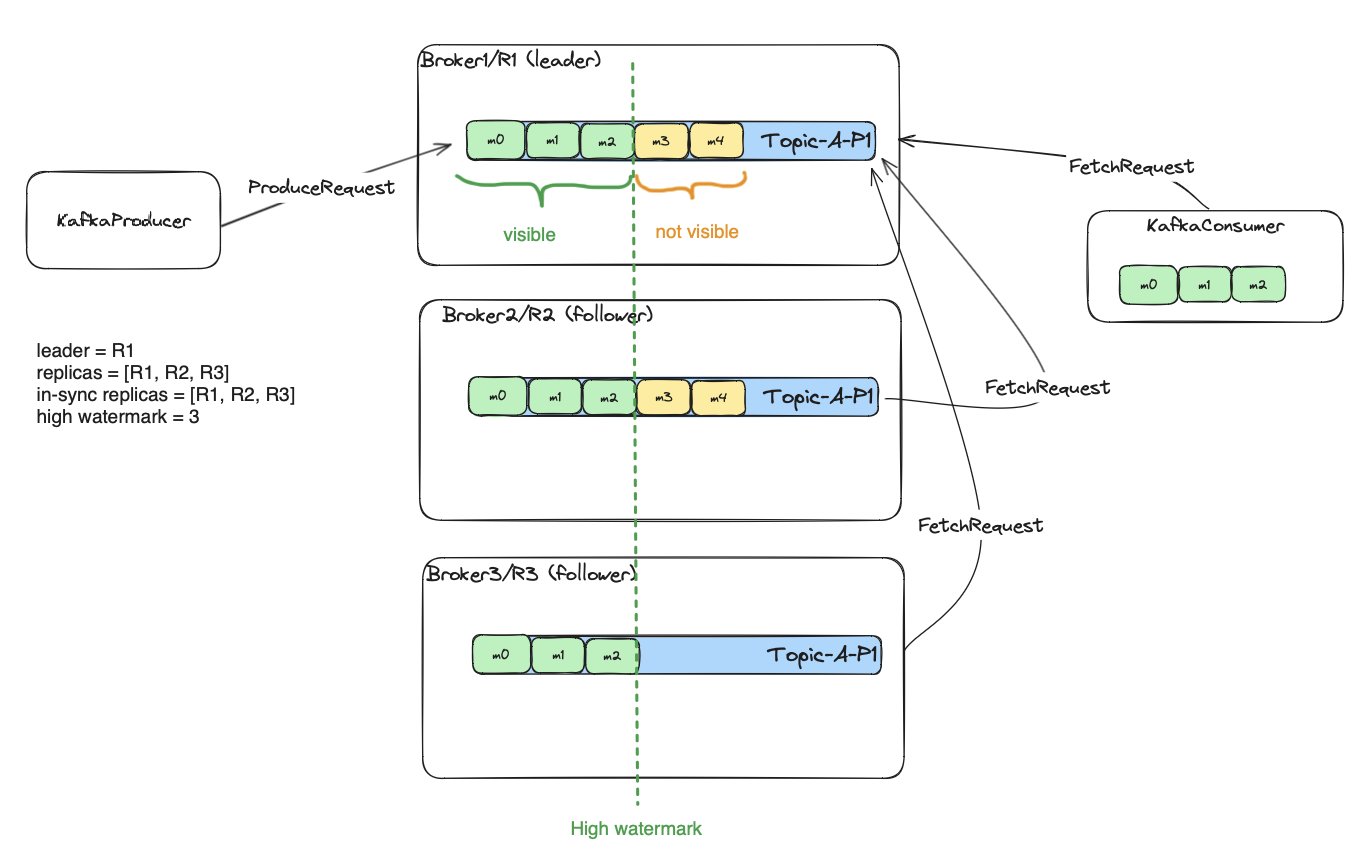

Consumer’s message visibility, watermark and committed messages.

The question that comes to mind when thinking about replication is: when the consumers can see the published message? The answer: when all in-sync replicas replicate the published message. Let’s investigate what that exactly means.

The picture above contains a topic with a replication factor 3. The producer published 5 messages with offsets: 0,1,2,3,4.

The messages 0,1,2 (green) were already replicated by all current in-sync replicas. The messages 3,4 (yellow) were replicated only by one

follower, so two out of three in-sync replicas have the copy. The offset below which all messages were replicated by all current in-sync

replicas is called a high watermark. Everything below that threshold

is visible to the consumers. So if the high watermark is at offset X, all messages visible to the consumers are < X.

This part of the log is also called the committed log. Consider the high watermark as an indicator of the safely

stored part of the log. This is an important thing to understand how Kafka provides high reliability in different failure

scenarios. We’ll get to that.

Let’s find out how and when exactly the high watermark is moved forward.

We have the following setup:

TopicA - partitions: 1 (one partition P1 for simplicity), replication factor: 3 (leader and 2 followers)

leader = R1

replicas = [R1, R2, R3]

ISR (in-sync replicas) = [R1, R2, R3]

I’ll use T[X] as the marker designating the time progression. Remember that LEO is the log end offset, and it is the next offset

that the replica doesn’t have yet for partition P. The leader moves the high watermark, and tracks each

of the follower’s LEO. I purposely show LEO and watermark only for a leader. In reality, each of the replicas track

its own LEO and copy high watermark from the leader. I will omit it for simplicity though.

----------------------------------T1-------------------------------------------------

KafkaProducer published 3 messages with offsets 0,1,2 to the leader R1.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2], HighWatermark = 0, R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 0, R3 LEO = 0

R2 | log = []

R3 | log = []

----------------------------------T2-------------------------------------------------

Replica R2 sends FetchRequest(offset=0) to the leader, and the leader responds with

messages it has in log. Note that R2 LEO doesn't change as the leader hasn't yet

been confirmed about persisting the messages by the follower. It has to wait for

the next FetchRequest(offset=3) to be sure that previous offsets were saved.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2], HighWatermark = 0, R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 0, R3 LEO = 0

R2 | log = [0,1,2]

R3 | log = []

----------------------------------T3-------------------------------------------------

The replica R3 sends FetchRequest(offset=0) to the leader, the leader responds

with messages it has in the log. The same situation as above. The replica didn't confirm

getting the messages yet. The high watermark cannot move forward.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2], HighWatermark = 0, R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 0, R3 LEO = 0

R2 | log = [0,1,2]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T4-------------------------------------------------

KafkaConsumer (client app) sends FetchRequest(offset=0) to the leader. The leader

doesn't respond with any messages because the high watermark is 0.

----------------------------------T5-------------------------------------------------

The replica R2 sends FetchRequest(offset=3) to the leader, the leader has no messages

having offset >= 3, so it doesn't return any new messages. But now the leader knows that

replica R2 persisted messages with offset < 3. The R2 LEO changes, and points to the

next message offset not present in the R2 log. The high watermark cannot move forward

since there is still one in-sync replica R3, which didn't confirm getting the messages.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2], HighWatermark = 0, R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 3, R3 LEO = 0

R2 | log = [0,1,2]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T6-------------------------------------------------

The replica R3 sends FetchRequest(offset=3) to the leader, the leader has no messages

having offset >= 3, so it doesn't return any new messages. But now, the leader knows that

replica R3 persisted messages with offset < 3. The R3 LEO changes to 3. All in-sync

replicas reached to the offset 3 (have their LEO=3). The high watermark can move forward

because all in-sync replicas confirmed getting messages with offset < 3. To be more

precise: the high watermark can progress when all in-sync replicas' LEO exceeds the

current high watermark. Because the HighWatermark = 0 and R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 3,

R3 LEO = 3, the leader can set the watermark to 3 as well. The [0,1,2] is now a committed

log and is visible to the KafkaConsumer clients.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2], HighWatermark = 3, R1 LEO = 3, R2 LEO = 3, R3 LEO = 3

R2 | log = [0,1,2]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T7-------------------------------------------------

KafkaProducer published 2 more messages with offsets 3,4 to the leader R1.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2,3,4], HighWatermark = 3, R1 LEO = 5, R2 LEO = 3, R3 LEO = 3

R2 | log = [0,1,2]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T8-------------------------------------------------

The replica R2 sends FetchRequest(offset=3) to the leader, the leader responds

with 2 messages [3,4] having offset >= 3. R2 LEO does not change on the leader

because it lacks the message persistence confirmation - the leader has to wait

for FetchRequest(offset=5) from R2 to confirm saving [3,4] messages. The high watermark

doesn't move forward. It can only progress when all in-sync replicas' LEO exceeds

the current watermark.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2,3,4], HighWatermark = 3, R1 LEO = 5, R2 LEO = 3, R3 LEO = 3

R2 | log = [0,1,2,3,4]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T9-------------------------------------------------

The replica R2 sends FetchRequest(offset=5) to the leader, the leader hasn't any

messages with offset >= 5. The leader changes its state for R2 LEO to 5 as it got

confirmation for saving messages with offset < 5. The high watermark does not

change as there is still a replica R3, which is in sync, and its

LEO <= current HighWatermark.

R1 (leader) | log = [0,1,2,3,4], HighWatermark = 3, R1 LEO = 5, R2 LEO = 5, R3 LEO = 3

R2 | log = [0,1,2,3,4]

R3 | log = [0,1,2]

----------------------------------T10-------------------------------------------------

KafkaConsumer (client app) sends FetchRequest(offset=0) to the leader. The leader

responds with messages having offset < HighWatermark: [0,1,2] which is a committed log.

Shrinking ISR

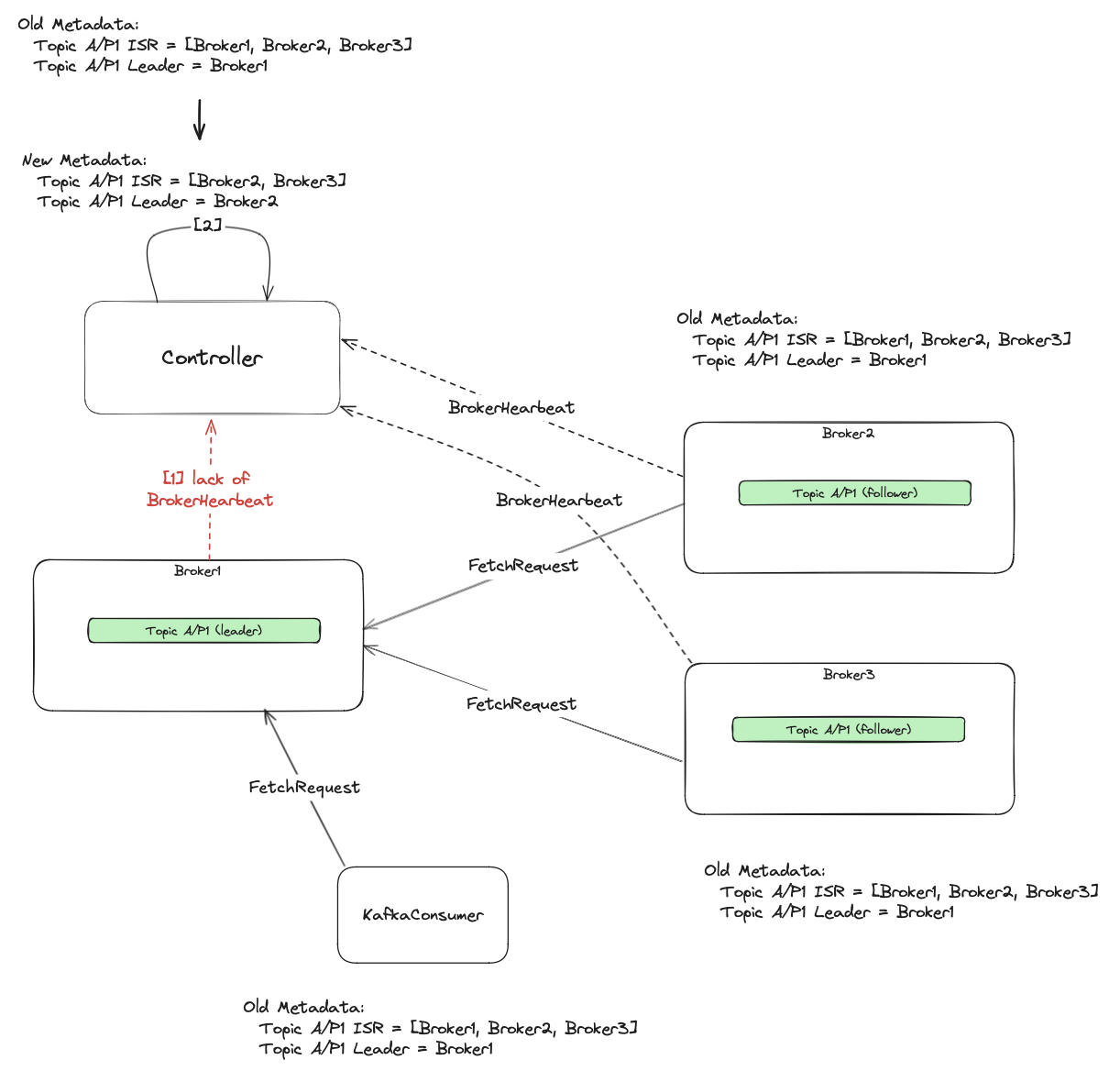

We said that in order to advance the watermark, all in-sync replicas must replicate the message. But what happens if one of the replicas becomes slow or even unavailable? Effectively, it can’t keep up with a replication. Without special treatment, we would end up with an unavailable partition - the HW couldn’t progress, and consumers couldn’t see the new messages. We can’t just wait for a replica until its recovery, this is not something a highly-available system would do. Kafka handles such a situation by shrinking the ISR. Do you remember the two conditions for a replica to stay in sync? I promised to explain what exactly happens when the replica falls out of the ISR. There are basically two scenarios when that happens:

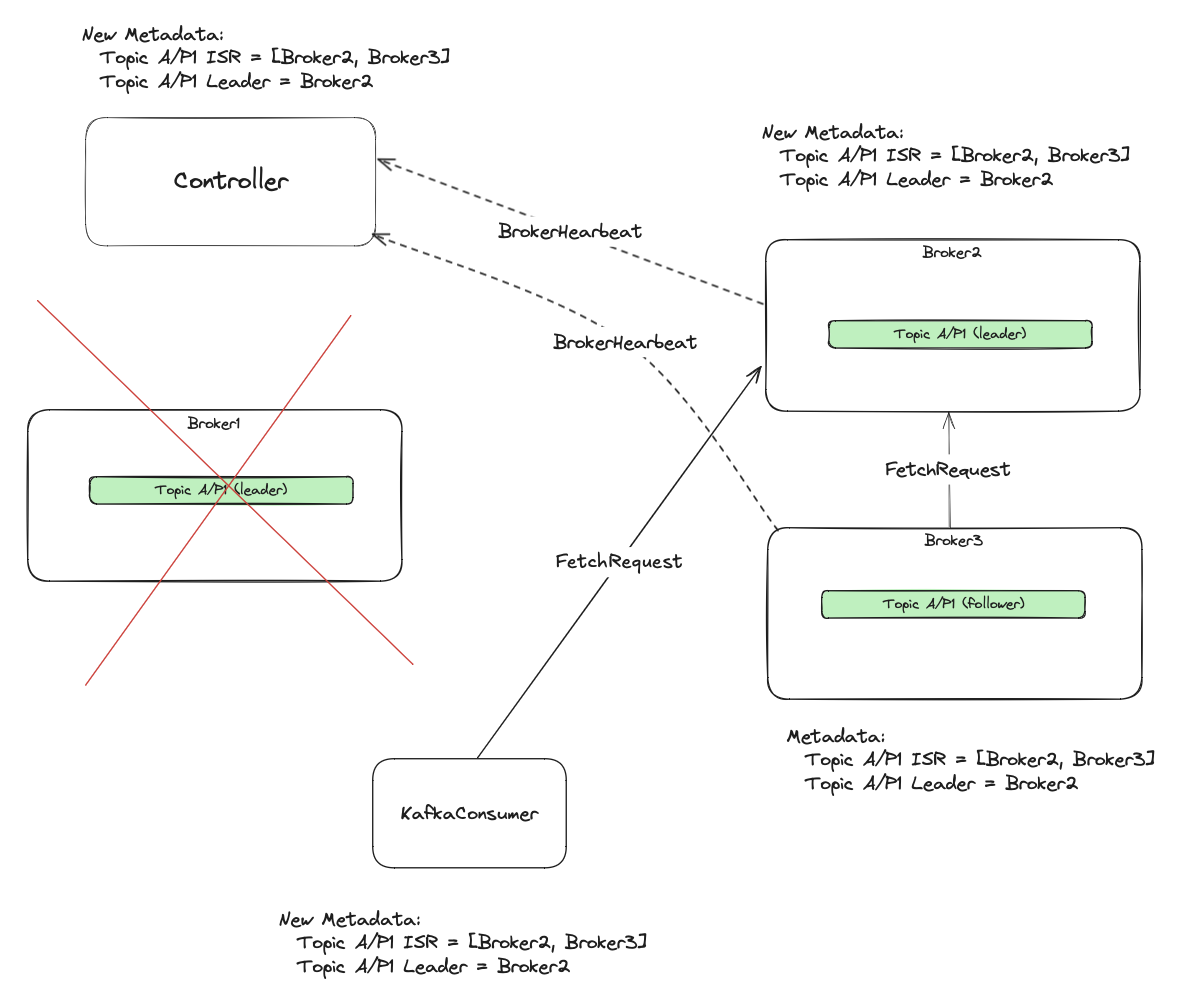

1) The unhealthy broker stops sending heartbeats to the controller. The controller fences the broker. That means it is removed from the ISR of all its topic partitions. This implies losing leadership for these partitions too. If the fenced broker is a leader for any partitions it handles, the controller performs leader election, and picks one of the brokers from the new ISR as a new leader. That information is then disseminated across the cluster using metadata protocol (from controller -> to other brokers -> and to clients).

The picture above shows the point in time when the current leader’s broker stops sending heartbeats [1]. The controller detects it and calculates the new cluster metadata [2].

The metadata then goes to the followers, so they can start fetching from the new leader. For picture clarity, I purposely didn’t draw metadata fetching requests from brokers to the controller and from consumers to the brokers.

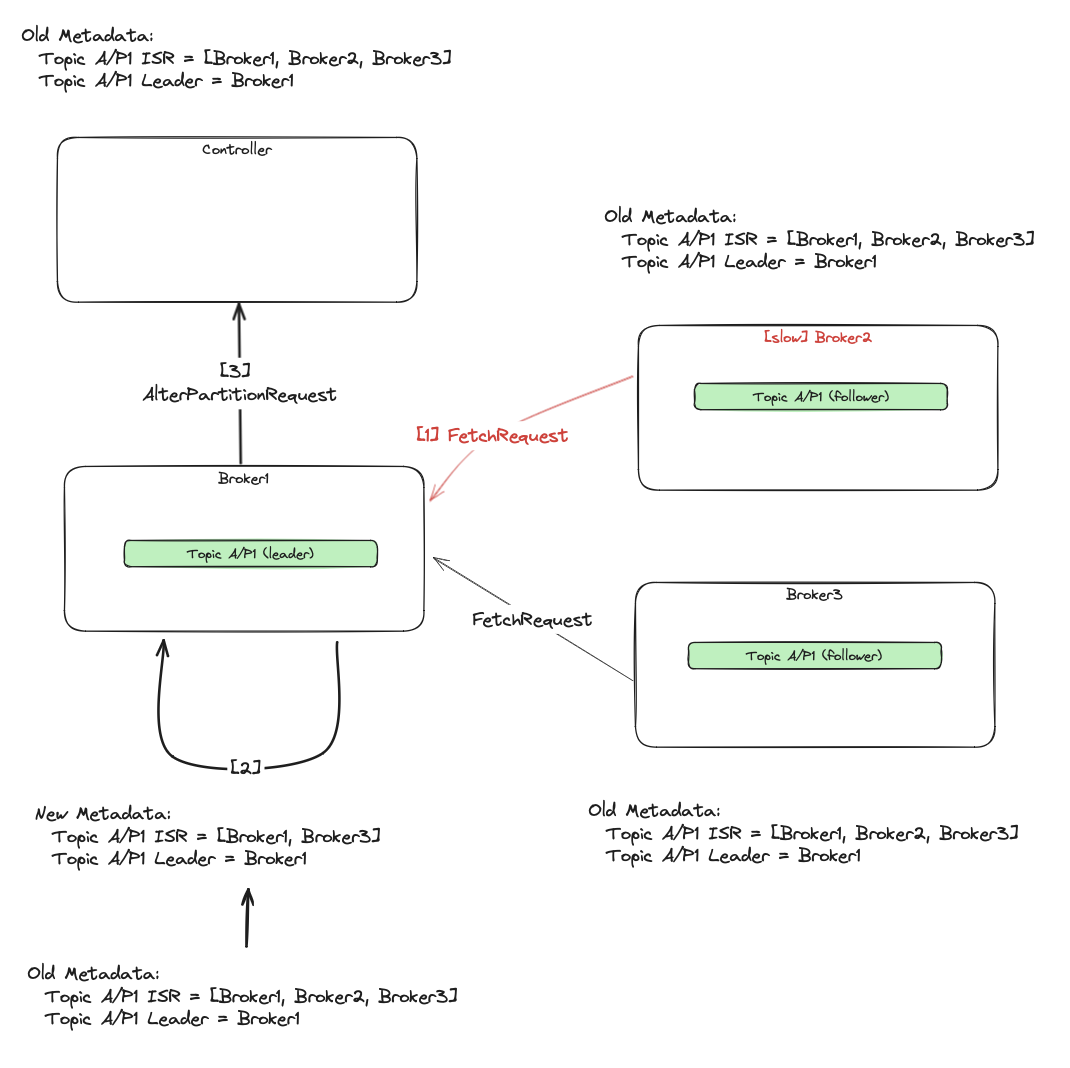

2) The second party allowed to modify the partition’s ISR (besides the controller) is a partition leader.

The leader removes slow or unavailable replicas from the ISR. It then sends the AlterPartitionRequest to the controller

with the new proposed ISR. The controller saves/commits that information in the metadata, which is then spread across the cluster.

Once the follower (Broker2) falls too far behind the leader [1], the leader removes it from the partition’s ISR [2],

and sends the AlterPartitionRequest to the controller [3].

Then metadata gets around the rest of the brokers and clients.

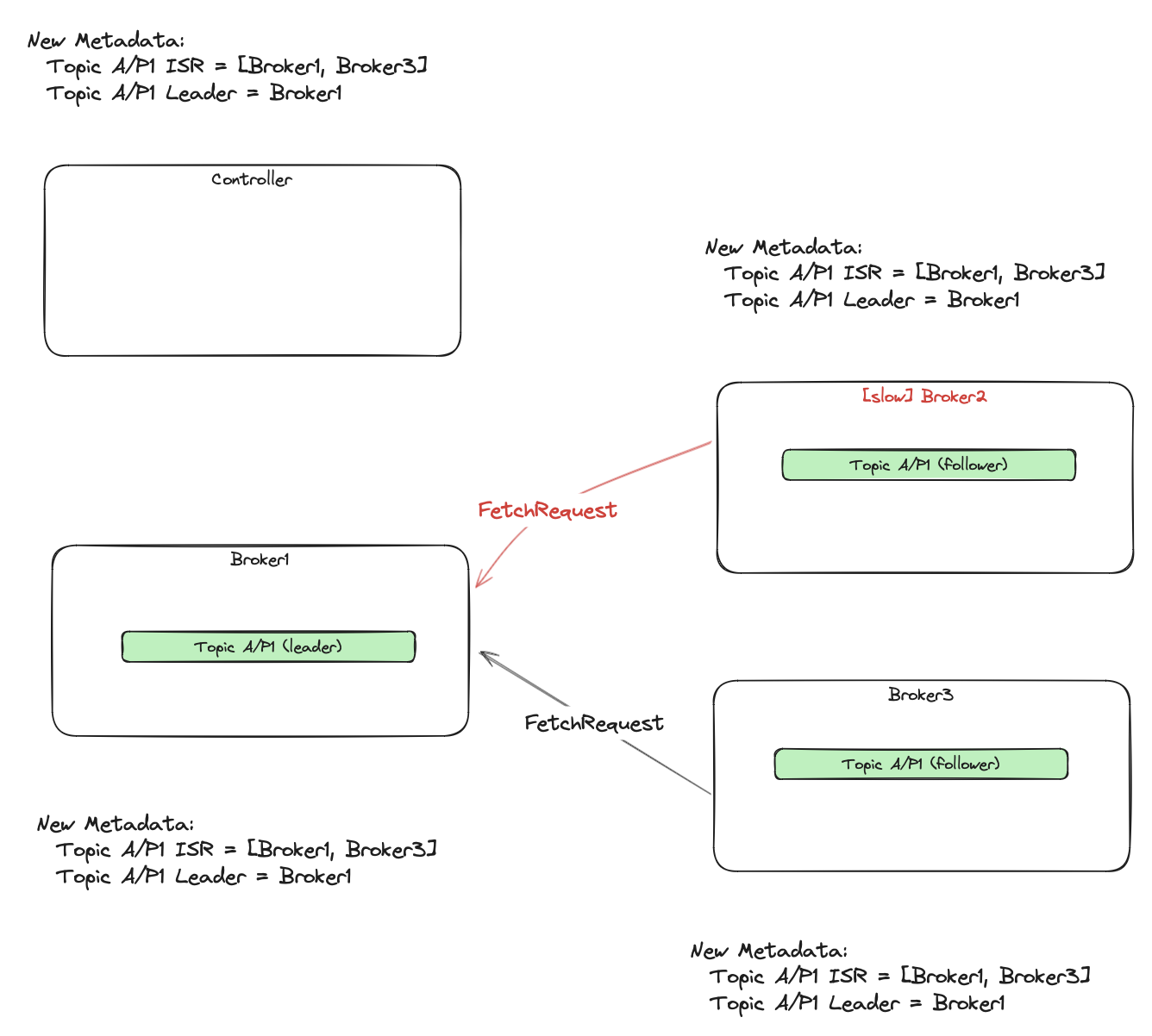

Expanding ISR

Assuming the partition currently has a leader, adding a replica to the ISR can be only done by that leader. Once the

out-of-sync replica catches up to the end of the leader’s log, it is added to the ISR by leader issuing the AlterPartitionRequest

to the controller.

What if there is no leader for partition? It can be the case that all replicas for example restarted. In this

case, the controller elects a leader and then saves that information in metadata (that will eventually go to the replicas).

The rest of the replicas will join the ISR by catching up to the new leader.

Min-ISR (minimum in-sync-replicas) and AKCs (acknowledgements)

In a distributed systems world, sooner or later you will come across a choice between

availability or consistency during failure scenarios. In Kafka, this choice is made by a collaboration of the

client - KafkaProducer, and the Kafka broker itself. Until now, we’ve mentioned that the KafkaProducer just publishes

messages to the leader, and then the replicas pull the new messages, so they eventually end up on a few independent brokers.

We haven’t specified yet when the producer should state that the message was successfully published:

- When just the leader saves the message on a local machine without waiting for replication from the followers? What if the leader crashed a short time after acknowledging, but before the replication happened?

- When all ISR replicas replicate the message? We know, that the ISR is a curated list of currently available and healthy partition replicas. We know it is dynamic. It can be even limited to the leader alone. It can be even empty!

- When some minimal number of ISR confirmed? How many brokers should get the copy, so we consider it safely replicated? This

is what a Kafka topic

min.in.sync.replicasproperty configures. The documentation can be found here.

The Min-ISR tells the partition’s leader, for how many of the ISR (including itself) it should wait before

giving a positive acknowledge response to the client. But this is not the end, I said that the KafkaProducer

participates in the decision-making process. That’s why we have the following producer configuration: acks.

I recommend reading the documentation, but in case you don’t:

acks=0- it is a fire-and-forget type of sending. We don’t care about saving the message in Kafka. We assume that most of the time the cluster is working fine, and most of the messages will survive.acks=1- wait until the replica leader stores the message in its local log, and don’t care if it was replicated by followers.acks=all- wait until the message is written to the leader and all in-sync replicas. If the number of ISR falls below Min-ISR (min.in.sync.replicas) the producer gets an error.

Note that in any case of acks=0/1/all, the consumers see messages only after they are committed.

The leader waits for all current ISR to advance the high watermark (HW), and consumers see messages

only up to the HW. Additionally, if the condition Min-ISR >= ISR is not met, the watermark cannot advance.

So even if message was published with ack=0/1, it is available for consumers when all ISR replicated up to that

message offset and the number of ISR is at least Min-ISR.

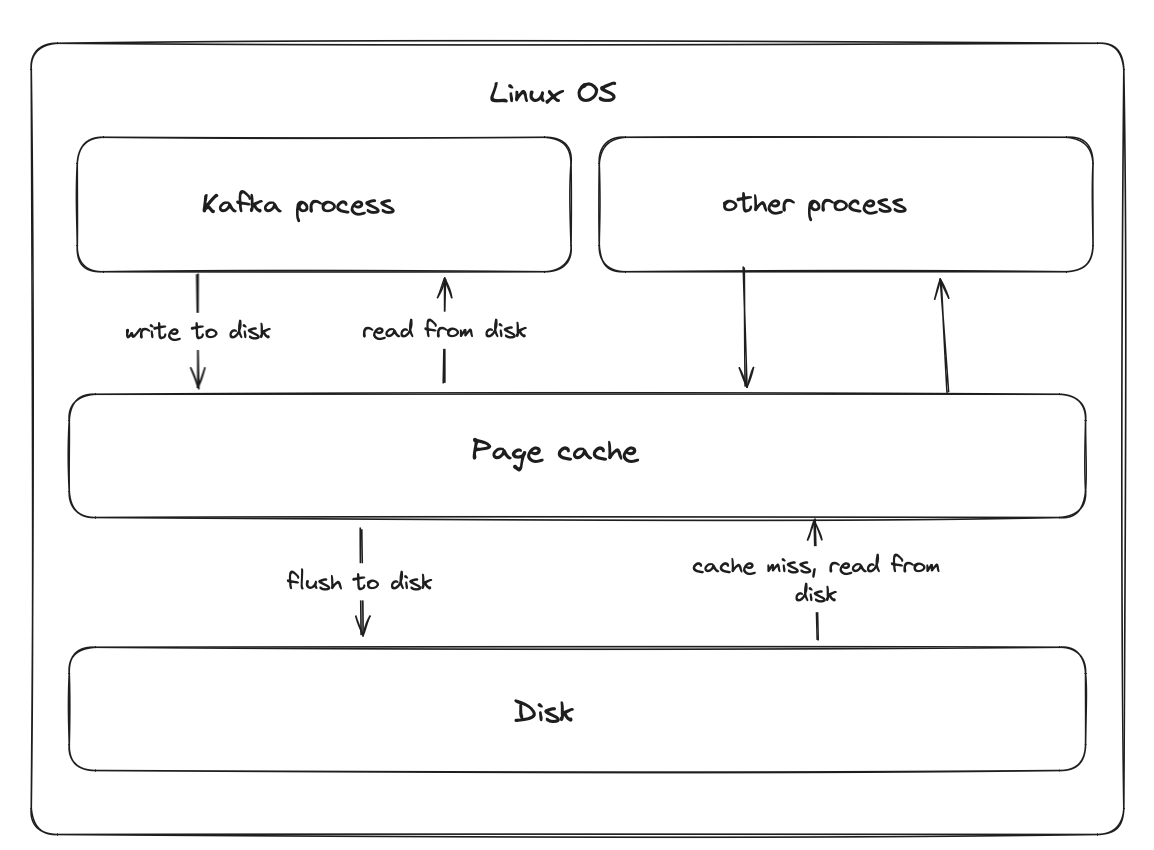

How Kafka persists messages

By default, Kafka broker doesn’t immediately flush received data directly to the disk storage. It stores the

messages in the OS I/O memory - page cache.

This can be controlled via flush.messages setting.

When set to 1 Kafka will flush every message batch to the disk and only then acknowledge it to the client. But then

you can see a significant drop in performance.

The recommendation is to leave the default config - thus not doing fsync. That means the message confirmed by the leader (acks=1) is not

necessarily written to disk. The same applies for acks=all - all ISR replicas confirm by only storing the message in the local OS page cache.

The OS eventually flushes the page cache when it becomes full. The flushing also happens during the graceful OS shutdown.

Because of this asynchronous writing nature, the acknowledged, but not yet flushed messages can be lost when the broker

experiences a sudden failure. Note, that the page cache is retained when the Kafka process fails but the OS remains fine. The page cache is managed

by the OS. The abrupt entire OS shutdown is something which can cause the data loss.

Leveraging the page cache provides improved response times and nice performance. But is it safe? And why I’m talking about

it during the replicaftion? Kafka can afford asynchronous writing thanks to the usage of its replication protocol.

Part of it is partition recovery. In the event of an uncontrolled partition’s leader shutdown, where some of the messages may

have been lost (because done without fsync) Kafka depends on the controller broker to perform leader election.

The objective is to choose a leader with a complete log - the one from the current ISR.

Preferred leader and clean leader failover

Each Kafka topic’s partition has a leader replica initially chosen by the controller during a topic creation. I previously explained the algorithm for assigning the leaders to brokers. The leader assigned at the beginning is called a preferred leader. It can be recognized by examining the output from Kafka topic details.

./kafka-topics.sh --describe --bootstrap-server localhost:9092 --topic=test

Topic: test TopicId: 2ZF_sUf2QjGHA5UJDFbY1g PartitionCount: 3 ReplicationFactor: 3 Configs: segment.bytes=1073741824

Topic: test Partition: 0 Leader: 2 Replicas: 2,3,4 Isr: 2,3,4

Topic: test Partition: 1 Leader: 3 Replicas: 3,4,1 Isr: 3,4,1

Topic: test Partition: 2 Leader: 4 Replicas: 4,1,2 Isr: 4,1,2

^

|

preferred leader ----

The preferred leader is the one placed at the first position in the Replicas list. The leadership can change. These changes are triggered

by a few actions, and one of them is a leader broker shutdown. During the graceful shutdown, the broker de-registers itself

from the controller by setting a special flag in the heartbeat request. Then the controller removes the broker from any partition’s ISR

and elects new leaders for partitions previously led by this broker. In the end, the controller commits this information to the metadata log.

The new leaders will eventually know about the changes via the metadata propagation mechanism. In the same way, followers find out from which node to replicate partition’s data. And the same happens for clients too - they use metadata to discover new leaders.

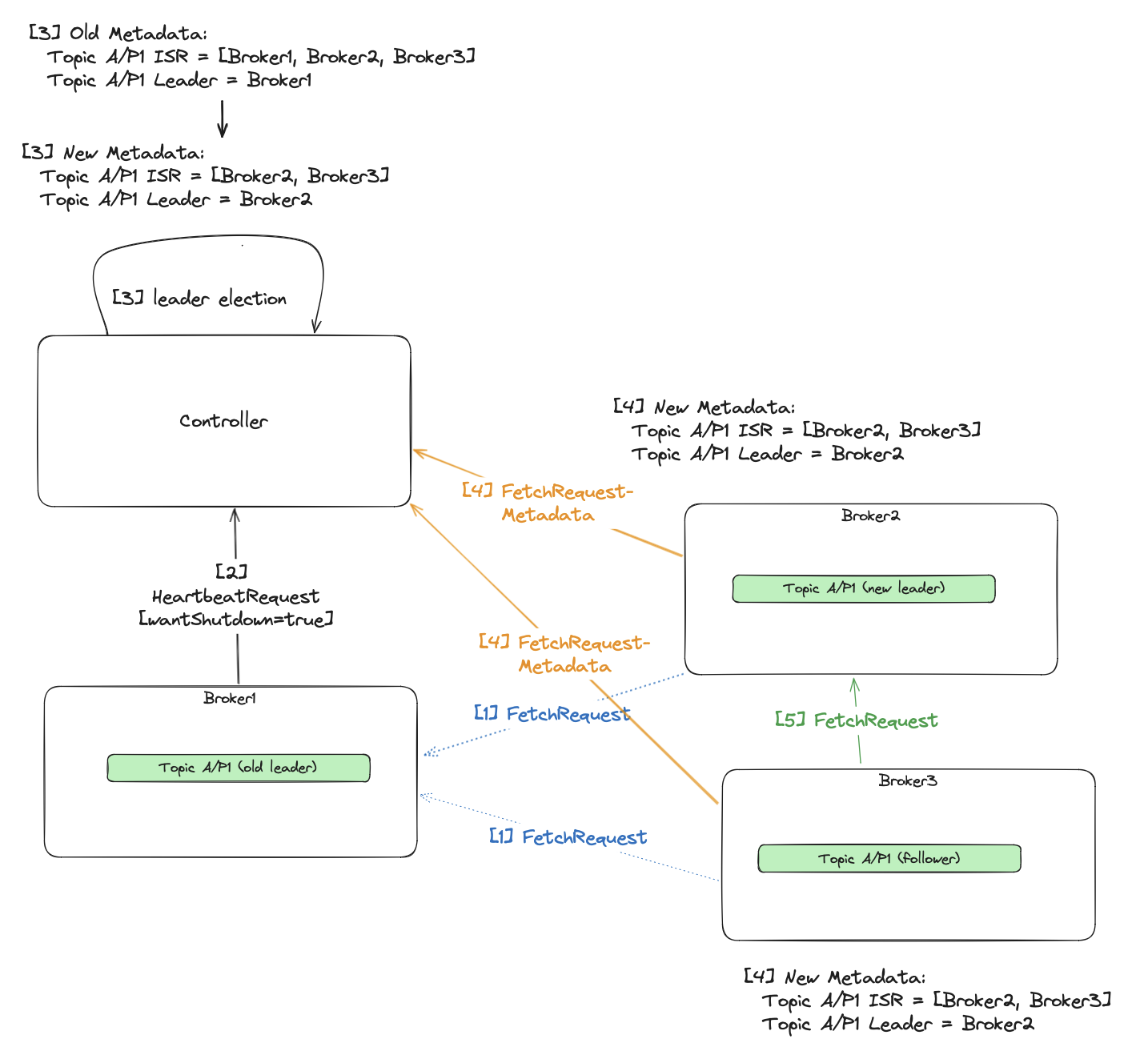

- Followers (

Broker2/Broker3) fetch fromBroker1being an old leader. Broker1sends periodicHeartbeatRequestto the controller. Once it wants to shut down gracefully, it sets a specialwantShutdownflag.- The controller seeing this flag iterates over all partitions with

ISRcontainingBroker1. Then it removes the broker from theISR, and if it was also a leader, elects a new one. Then it writes these changes to the metadata log. Broker2/Broker3learns about the changes by observing the metadata log via periodic fetch requests from the controller.- Once the

Broker3detects a new leader, it starts pulling from it. - Now

Broker1can shut down.

Another reason for changing a leader is the current leader’s broker failure. The failed broker stops sending

heartbeat requests to the controller. Once the broker.session.timeout.ms passed, the controller removes the leader from

any partition’s ISR, elects a new leader from the rest of the ISR and commits that change to the metadata log.

These cases are also called clean leader elections because we choose a leader from the ISR, and brokers in the ISR have to have a full committed log. But we can find it in a much less comfortable situation.

Unclean leader election

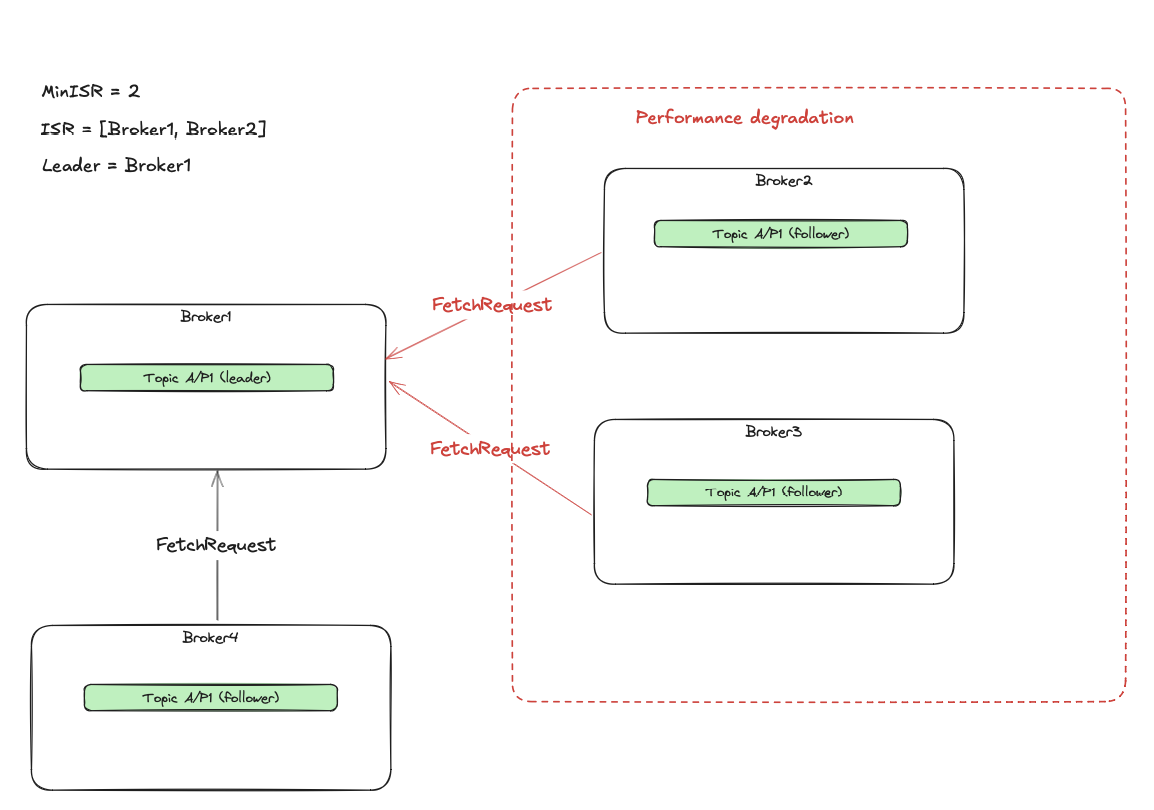

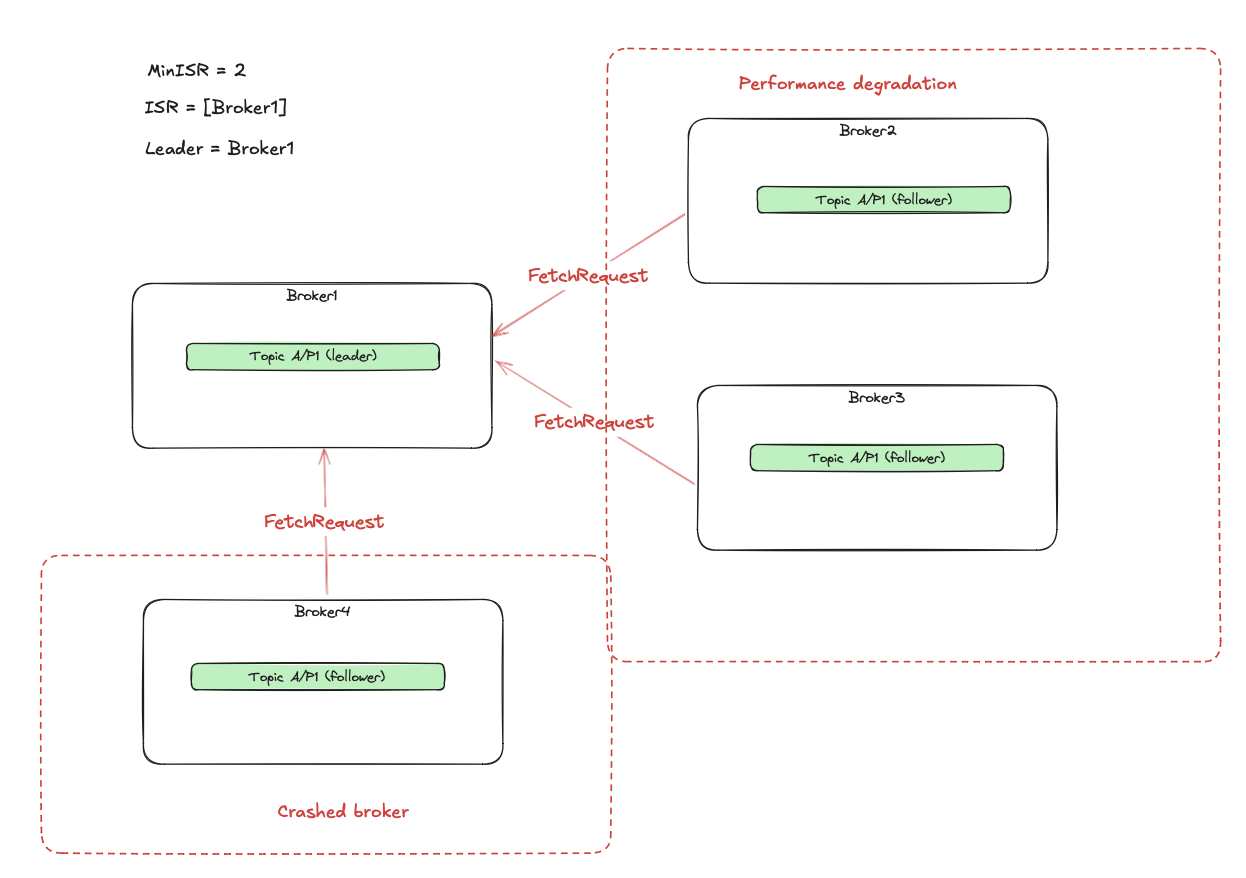

Consider a topic with a replication.factor=4, min.in.sync.replicas=2 and single partition A for simplicity.

The current in sync replicas count is ISR=2 (Broker1/Broker4). We have two brokers (Broker2/Broker3) with performance degradation,

so they end up outside the ISR. The ISR >= MinISR condition is met, so any ACK=1/all produce requests work fine.

What happens when the 3rd broker (Broker4) crashes?

- The producers with

acks=allget errors becauseISR < MinISR. - The

acks=1still works fine. - The high watermark cannot progress because

ISR < MinISR. No more messages can be committed. Because of that, consumers don’t get any new messages. - Effectively the partition is available only for writes with

acks=1, but not foracks=alland reads.

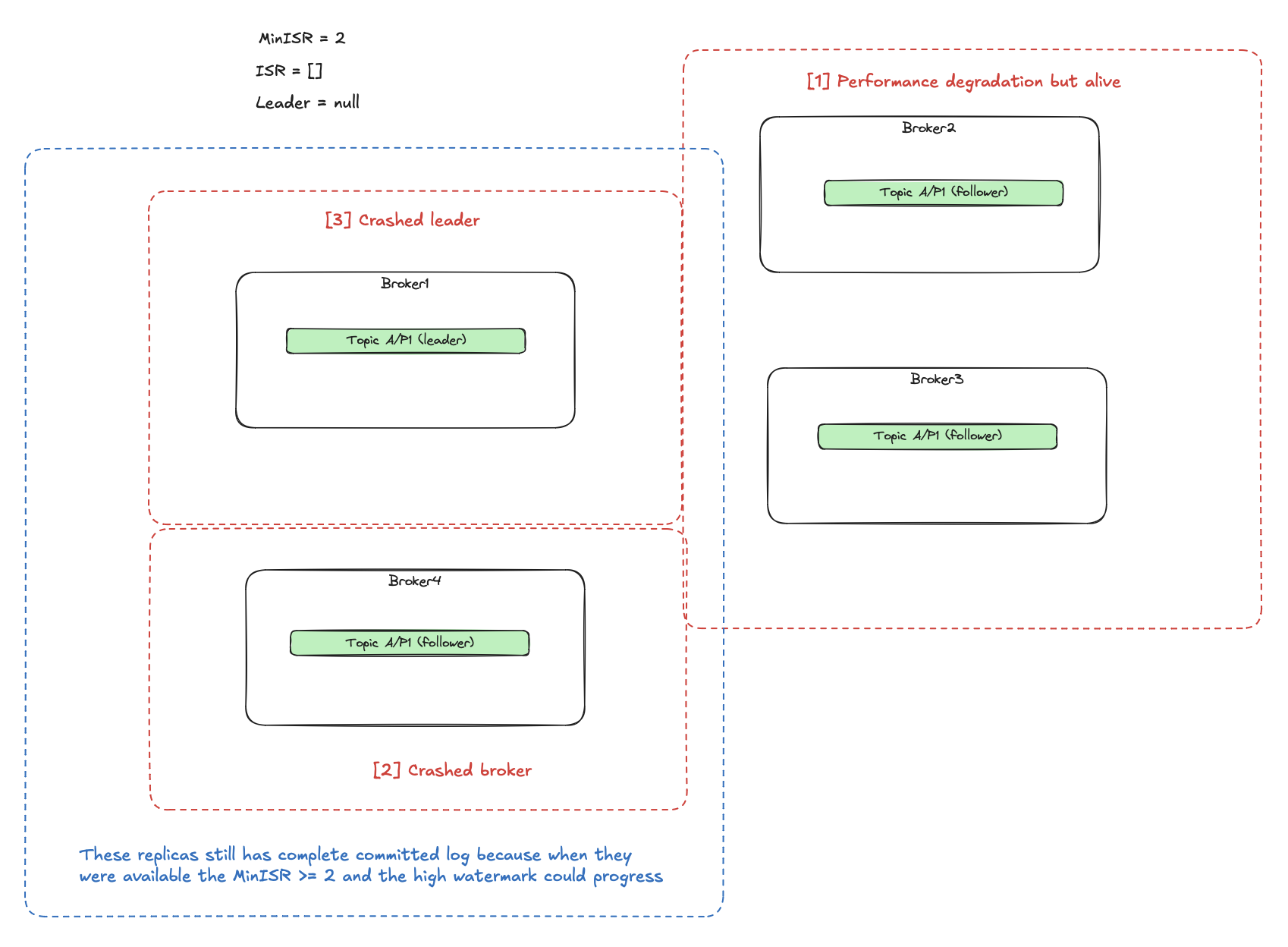

What happens now when the current leader (Broker1) fails? It was the last in sync replica. The leader election described so far

assumed that the next leader can be only selected from the ISR set (clean election) - but there are no more ISRs.

The partition becomes completely unavailable. What choices do we have in this situation?

- We care about not losing committed data, and we have to wait for at least one of the previous

ISRreplicas to become available again. Which are these? The last leader (Broker1) and the broker which failed before (Broker4) because at that time theISR >= MinISR(the new messages were still accepted and committed). This is a broad topic described as the Eligible Leader Replica, and it is currently under development. - We care about making the partition available even if it means losing some data. We still have 2 replicas (Broker2/Broker3) which

were outside the

ISRfrom the outset and may not have all committed events. But at least they are alive, so we can elect one of them as the new leader. This will cause the rest of the replicas (including Broker1/Broker4 after recovery) to truncate their logs to that what the new not up-to-date leader has. We can enable this by settingunclean.leader.election.enable=trueon a topic.

Availability vs consistency

Setting all previously mentioned configurations:

- number of acknowledgements

acks - minimum in-sync-replicas (

min.in.sync.replicas) - number of replicas (

replication.factor) - unclean leader election (

unclean.leader.election.enable)

requires understanding how they affect availability and consistency. Before configuring topic, start by answering the question: do you accept losing any data? Do you accept that some of the produced message may never be delivered to the consumers even when Kafka responded successfully during publishing? Most of the time, Kafka will work fine, but you have to prepare for the hard times too:

- broker disk failures

- slow network

- network partitions (some of the brokers cannot communicate with others)

- broker ungraceful shutdown

- broker machine disaster

What is more important to you when the above conditions arise?

Availability - being able to produce messages even though some of them may be permanently gone.

Consistency - stop producing and throwing errors when there are not enough replicas to provide expected durability.

When you know the answer, you can lean toward a set of configurations adjusted to these requirements.

Availability:

acks=1- only the leader confirms during producing, there is no need to wait for a more replicas before acknowledging the messages. Note that this concerns only write availability. The leader does not return messages to the consumer until they are replicated to the currentISR. If theISR < Min-ISRthen the high watermark cannot progress, and the consumption stops despite successful writing.- lower

min.in.sync.replicas- as mentioned in the previous point, foracks=1, theMin-ISRdoes not affect producing, but will always affect consuming. The consumers can only fetch committed messages. These are messages with offsets below the high watermark, thus replicated to at leastMin-ISRnumber of brokers (the high watermark progression depends on conditionISR >= Min-ISR).Before blindly setting it to 1, note that while higher

Min-ISRputs a restriction (and delay) on a consuming process, it also increases predictability for consumers. They get messages only once these are stored on multiple machines. For example, reprocessing the same topic multiple times, interleaved with the brokers’ failure, results in a more consistent view of messages. - In case of using

acks=all, loweringmin.in.sync.replicaswill increase the producing availability as well. - higher

replication.factor- the more replicas you have, the more of them can serve as theISR. Forack=1, a higher number ofISRmeans a broader choice of the valid replica during leader failover. Foracks=all, moreISRmeans greater chances thatISR >= MIN-ISRwhile some replicas are unavailable. However, when all nodes are healthy (thus are inISR), more replicas means waiting for a higher number ofISRreplicas before committing the message. And obviously, brokers have more work to do because of replication. - unclean.leader.election.enable set to

true- when the subset of nodes with complete committed data (ISR) failed, you favor electing not up-to-date (outside ofISR), but alive node as the leader, rather than waiting for one of theISRto recover.

Consistency

acks=all- leader waits for all replicas in the currentISRbefore acknowledging the client.

IfISR < MinISRthen it returns errors. The visibility for consumers and high watermark progression is the same as foracks=1- higher

min.in.sync.replicas- should be lower thanreplication.factorto have some space for availability as well - higher

replication.factor- same as in the availability section - unclean.leader.election.enable set to

false- only replicas with a complete committed log (ISR) can become a leader. When not currently available, the whole partition is nonfunctional, but will not lose data when at least one of theISRrecovers.

Performance

We graded different configurations in terms of availability and consistency, but they have an impact on the performance as well:

acks=1- causes better write latency as the leader doesn’t wait for allISRto confirm messages. The consumer still has to wait for the fullISR. More info about e2e latency here.acks=all- increased write latency. On the consumer’s side, nothing changes.replication.factor- higher number of replicas indicates higher network, storage, and CPU utilization. The brokers have much more work to do because of the replication. Finally, the end-to-end latency will increase too.min.in.sync.replicas- this does not affect the performance. In any case, the leader waits for all currentISRwhen producing withacks=alland moving a high watermark. TheMinISRdoes not affect write latency, end-to-end latency or throughput.

Configurations examples

Now I’ll provide you a few examples showing the implications of mixing different configurations.

The unclean.leader.election.enable is false.

replication.factor=4,min.in.sync.replicas=3,acks=all- this config provides high consistency at the cost of availability and write latency. Each message is replicated to at least 3 brokers (including the leader) before getting a successful response. During the healthy brokers’ conditions, theISR=4, soack=allwill wait for all 4 brokers. One of the brokers can fail (ISR=3), and we still haveISR >= Min-ISRcondition met, so we still can produce new messages. Losing one more broker (ISR=2) affects availability, as theISR >= Min-ISRwon’t apply anymore.

When theISR=3, and the partition is still available for writes, it can survive up to 2 further replica failures without losing data. In such an extreme situation, there still would be one node with a complete committed log, which would be elected as the leader. The rest of the brokers could replicate from it after the recovery.

In a more common scenario, (ISR=4) we would survive up to 3 replicas crashes.

To sum up: we can tolerate up to 1 broker crash while still being available for writes, and then 2 (Min-ISR - 1) failures without losing data.replication.factor=4,min.in.sync.replicas=2,acks=all- moderate consistency and availability. We can tolerate up to 2 unhealthy replicas while providing availability, but then we can lose only one additional partition (Min-ISR - 1) without losing data.replication.factor=4,min.in.sync.replicas=2,acks=leader- we favor availability over consistency. The leader responds successfully after storing messages in its local log before replication to the rest of theISRhappens. By using this configuration, you accept the possibility of losing some events. The lost are those acknowledged by the leader, but still not yet replicated by theISR- a non-committed part of the log. The reality is that you can lose messages in more scenarios than just leader failure. As the author of the post shows, the networking problems are even worse (the post investigates Kafka with Zookeeper). Nevertheless, once we accept the possibility of occasional data loss, we get very high availability: we can write messages even without 3 brokers. Note that consumers will see data once it is replicated by at leastMin-ISR=2brokers.replication.factor=4,min.in.sync.replicas=1,acks=all- we favor availability over consistency in case of emergency, but when the cluster is healthy, we want to replicate to a higher number of replicas - currentISR. When all replicas perform well, theISR=4, and the leader will acknowledge events when allISRreplicate. The messages are then available for consumers after replication to the fullISR=4. In case of emergency, theISRcan even shrink to the leader itself, and we still be able to produce/consume (because ofMin-ISR=1). This may seem like a non-practical scenario: why enforce higher consistency when everything goes well, but when not, just forget about safety and accept losing data? Compared to anyacks=leaderconfiguration, this will be more reliable during leader restarts.

For example, consider a scenario when the leader rebooted ungracefully, and the rest of the replicas were fine at that time. The leader could acknowledge some messages before the restart, by writing them to the page cache, which is not immediately synchronized to disk. If the producing was made withacks=leader, the leader didn’t wait forISRbefore acknowledging, which when followed by the shutdown could end up with a data loss. But in our case, the producer usedacks=all. The leader waited for all currentISRbefore acknowledging. This means that the new leader from the currentISRhad to have all acknowledged messages - no data loss.

Conclusions

We’ve covered a lot of replication stuff, but it is still the tip of the iceberg. There are plenty of mechanisms that Kafka implements to provide safety, availability, and good performance. In case you are interested in discovering the lower parts of this iceberg, I recommend to read the following materials:

- Kafka replication documentation.

- Kafka improvement proposal (actually in progress) enhancing replication correctness.

- Really interesting (and detailed) set of posts about the internals of Kafka replication.

- Series of blog posts about scenarios when Kafka can lose messages (these are for the Kafka version before introducing the KRaft controller).

- A talk describing how hard it was to implement a safe Kafka replication protocol. The author talks about different mechanisms preventing from losing messages.

- Replication for Kafka control plane - KRaft. We talked about replication between usual brokers but omitted discussion about replication between Kafka controller nodes.

- Why Kafka does not need fsync to be safe.

- And of course Apache Kafka Github repository.